Eat Like a Horse

Estimated 0 min read

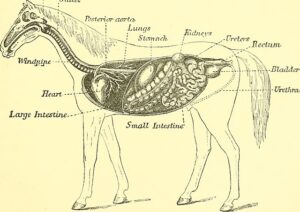

What you need to know about your horse’s digestive system

Horse Digestive System–Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

A horse’s digestive system is complex, and very different from humans. For that matter, it’s unlike that of many species. As a prey animal, being hunted for their meat rather than being the hunter, they have naturally formed a roving, nomadic lifestyle. As a result, theirs is a life of wandering and grazing, staying constantly on the move. Until mankind got involved! Even more important, horses evolved to eat small meals for at least 16 hours each day. To support this lifestyle, horses are non-ruminant, simple-stomached herbivores, which means, they mainly eat plants. By contrast with cattle, goats, deer or sheep, horses ferment fibrous feed in their hindgut. Consequently, for horses, the fermentation process takes place in the large intestine. While, on the other hand, ruminants (cattle, goats & sheep) ferment in their foregut’s rumen and their multicompartmental stomachs. (Did you know that a cow’s stomach has 4 compartments, each with a vital role?) Accordingly, a horse’s stomach functions more like a human stomach, one compartment.

Read on to find out more about the horse’s gastrointestinal tract—and how this can improve your horse’s health and life. What’s more, we’ll describe the various parts of a horse’s digestive system in a way that will help you help your horse!!

The 4 Foregut components in a Horse’s Digestive System are as follows:

The Mouth

Watch out! A horse’s mouth produces gallons of saliva

First we can visualize the horse’s mouth that includes the following: tongue, teeth and salivary glands. Once a horse brings food into his mouth with his lips, he chews, or masticates, the material into smaller pieces. A horse uses his lips carefully to sort out good food/fodder from the less desirable. Those sensitive lips can detect, many a time, whether there is a pill in that handful of food that his owner has just offered! We’ve all watched those lips eat the food and LEAVE the pill. After your horse has chomped his food into smaller pieces, these mix with the saliva for the first step of the digestive process. Even more, this saliva makes it easier for food to pass through the esophagus, and it also acts as a buffer for stomach acid.

In truth, a horse can produce 9 or 10 gallons of saliva each day, which helps lubricate the food and create a “bolus”. The purpose of the food bolus is to create a round mass of “oiled” food that is easy to swallow.

Secondly, the Esophagus

Once chewed and moistened, the food boluses pass to the stomach via the esophagus. The esophagus is 4 to 5 feet long and moves food to the stomach in one direction with muscular contractions called peristalsis. Check out this for an amazing fact: the horse indeed has a very small stomach. It is only capable of holding around a 2-4 gallon capacity. Imagine that when compared to the total weight and size of your horse!

Consistently provide water for your horse

Interestingly, a horse’s soft palate does not allow food or water to return back to the mouth (horses can’t regurgitate). Peristalsis only goes one direction. If a horse has a reflux issue, the food and saliva have to exit out via the nostrils. Horses are not able to vomit.

An esophageal obstruction is known as Choke. When this happens, you will see feed coming out of your horse’s nostrils. With Choke, a horse can breathe, but they can’t eat or drink. Take note: this is an emergency requiring veterinary attention. You can reduce chances of Choke by keeping water constantly available and maintaining your horse’s teeth regularly. Moreover, anything that you can do to avoid your horse rushing into eating reduces the risk. Choke can happen if beet pulp is not soaked sufficiently. Too much overly dry fiber gets into your horse’s system without sufficient water or saliva and presto!…you have a Choke situation.

Add to this the presence of a muscular ring called the cardiac sphincter that allows food to exit the esophagus and enter the stomach. This is a one-way valve, preventing already-digested food and gas from re-entering the esophagus.

Not much digestion occurs in the esophagus.

Third Pit Stop – the Stomach

Horse filling his stomach

As we mentioned, a horse’s stomach can only hold about 2-4 gallons of fluid and makes up about 10% of the total digestive tract. In fact, out of all domestic animals, a horse has the smallest stomach in relation to its size. This explains why small, frequent meals are best for your horse.

The main function of a horse’s stomach is to mix and store food before releasing it into the small intestine. Part of this process is achieved by Pepsin and Hydrochloric Acid that are secreted in the stomach to help begin breaking down the food. Note: minimal nutrients are absorbed in the stomach.

When a horse’s stomach is empty, the pH of the organ is lowered. This is not a good situation for your horse. A lower pH means increased acidity which can in turn increase the risk of forming gastric ulcers.

And finally the Small intestine

The small intestine, which is comprised of the duodenum, the jejunum and the ileum, makes up about 30% of a horse’s digestive system. Measuring about 70 feet long, the small intestine moves food through it quickly, at about 1 foot per minute. Digested food is then passed through to the cecum swiftly—around 45 minutes after a mealtime. The amount of nutrients absorbed varies depending on the volume of feed and how fast it passed through this intestine. So, again, smaller meals increased nutrient absorption.

Most carbohydrates, protein and fat are digested by enzymes in the small intestine. These enzymes: amylase enzymes for starch, lipase enzymes for fat, and protease enzymes for protein—are produced in the pancreas or small intestine. Their task is to process the nutrients into glucose, glycerol and fatty acids, and amino acids. Since horses don’t have gallbladders, the liver supplies bile to assist in fat digestion.

However, if food passes this far without being optimally digested, that undigested starch goes on to the hindgut. Such incidences can happen when large amounts of food are fed at one time, particularly if it includes cereal grains with a seed coat. There in the hindgut, bacteria will ferment any undigested starch. But this can cause too much lactic acid production and accumulation. As a result, issues such as hindgut acidosis, colic, metabolic acidosis and laminitis. How many times can we mention this? Small meals, fed often, and paired with quality forage/hay, can reduce these issues.

The 5 HindGut components in a Horse’s Digestive System:

The Large intestine / Hind Gut

Horse foraging grass

In fact, a horse’s hindgut is large in comparison with ruminant animals like cattle. The hindgut digests feed on a microbial level through fermentation. It consists mainly of dietary fiber from the forage (hay and grass). Likewise, its job is to take care of food that has skipped the processing step in the foregut. This activity produces volatile fatty acids, which supply the horse with energy. Fermentation in the hindgut also produces methane, carbon dioxide and water. The hindgut aids in water reabsorption.

But microbes in the horse’s hindgut are highly sensitive to diet and lifestyle changes. This is why changes to your horse’s diet—even as innocent as switching the source of hay—plan to do this over a time period of 7-10 days.

In addition, the equine digestive system has many twists and turns. Likewise, it narrows in multiple locations, which increases the risk of impactions and blockages by the dense, fibrous plant material that it routinely handles.

The Cecum

Next in the order is the Cecum. Digested feed passes from the large intestine into the Cecum through the ileocecal valve. The Cecum is 12-15% of the digestive tract. It’s like a large, muscular mixing vat that can hold 7-10 gallons of food/fluid. Accordingly, this organ slows down the digestive process so that microbes can digest fiber for up to seven hours.

There’s a lot of movement in the cecum. The unfortunate result of all of the twisting or displacement within and around the organ is a “twist” in the cecum or intestine that can lead to colic. Moreover, excess gas from a disturbed microbiome can close the ileocecal valve, a further cause of colic. In fact, we commonly refer to this as “gas colic”.

The Large colon

Seek out our vet for horse digestive issues

All told, the large and small colon together comprise 40-50% of the horse’s digestive tract. The large colon can hold up to about 20 gallons of matter. Generally speaking, digested food takes two to three days to pass through it entirely.

In addition, the large colon folds backwards and becomes narrower in diameter at a point called the pelvic flexure. This allows for more time for microbial digestion, but it also allows heavy particles such as sand to settle out of the digesting food into the colon. As a result, the deposits of sand may lead to Impaction colic or, worse, tissue necrosis can occur as a result. Speak with your Vet on this one. Your veterinarian can easily palpate rectally to see if your horse is at risk for impaction colic.

The Small colon

Moving onto the small colon where the main function is water absorption. It’s also where fecal balls form. They then continue their journey into the last 12 inches of the organ known as the rectum.

And, finally, the Rectum

And now we have the final part of the horse’s digestive system. The rectum is the outlet for feces that are the result of unwanted leftovers from the digestive process. These feces, as we explained earlier, may include seed coated grains such as whole oats that did not get broken down in the digestive process.

What does this mean for your horse’s care and health?

Consider feeding hay before grain. The intake of hay means more saliva production in your horse’s stomach. And what does saliva do? It’s a first-class stomach buffer! This may translate into fewer equine stomach acid issues and a happier horse.

Happy horse? Happy rider!

In summary, to help your horse achieve optimal digestion:

- Feed at regular times, with regular amounts of feed.

- Feed high quality forage and concentrates.

- Your horse’s diet should be a minimum of 50% forage, preferably more.

- Avoid large meals of grains or concentrates—you should feed smaller, more frequent meals instead.

- Make any changes to your horse’s diet slowly.

- Offer fresh, clean water to your horse at all times. It’s the oil for the engine!

- Maintain regular dental care and deworming routines.

Banixx Horse Blog

To learn more about Banixx and our equestrian projects we support please followour horse blog. Better yet, as a horse lover, read one of stories on thesmallest horse in the world. Or on a more serious note, learn how toget your horse to drink more water.

We hope you found this article helpful and if your horse ever gets anywounds,cuts.scratchesorwhite line disease, we hope you keep Banixx Horse & Pet Care in mind. We have information on topics such as your horse’sweight? Or, tip ways tomaintain your horse’s tailor the miracles ofacupuncture for your horse..yes. we’ve got these all covered for you! Need your own Banixx, clickhereto find out where to buy it!

Sources

https://www.extension.iastate.edu/equine/blog/dr-peggy-m-auwerda/digestive-anatomy-and-physiology-horse#:~:text=Horses%20are%20non%2Druminant%20herbivores,and%20rectum%20(figure%201)

https://ohioline.osu.edu/factsheet/1022